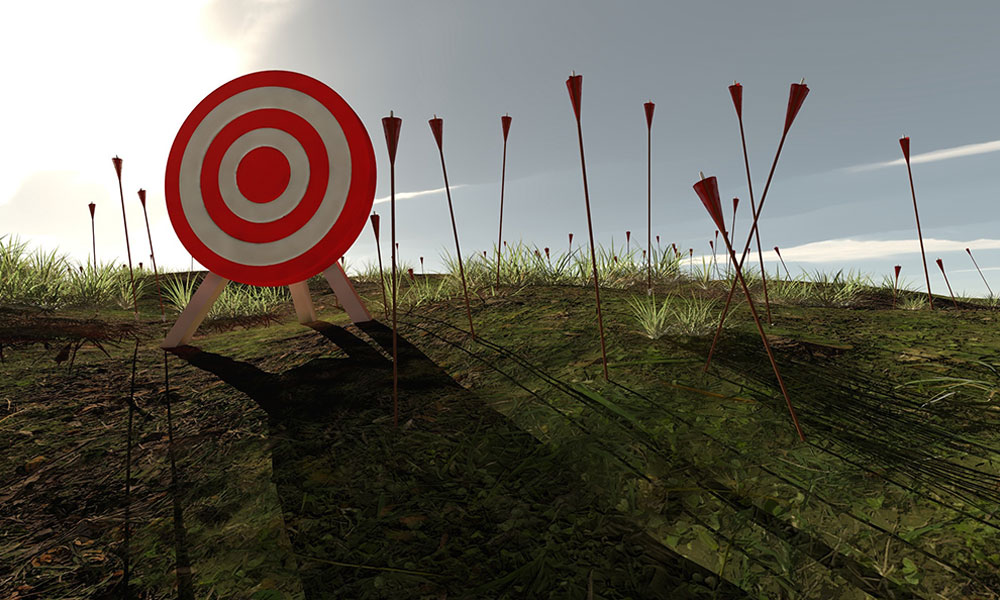

So often in discussions, I find our team members asking – “So, what is the industry best practice?” These ‘best practices have long become the Holy Grail of determining what and how to improve. The questions invariably revolve around – do you know what the best practices are? Is what you are doing a best practice? Who is best at it? How quickly can you adopt one? And so, not surprisingly, many consulting firms have made a very good business of peddling these practices.

But let’s stop for a moment and consider this – how do you really know whether or not something is a ‘best’ practice? Just because others are doing it (and arguably better), does it make it the best? And if not, are you doing more harm than good by just aping them?

Drawing from this, my message today is on the perils of best practices – could an over-focus on best practices actually constrain or limit us?

Why do we follow best practices? To learn from people who presumably got it right and to bring in more outside-in perspectives. The intentions are noble. More often than not, it is about learning and replicating. But that in itself is also the biggest problem. By definition then, best practices propagate legacy-based thinking. They can stem innovation.

Leadership advisor, Mark Myatt, in his Forbes article Best Practices – Aren’t, argues that there is no such thing as best practices: “The reality is best practices are nothing more than disparate groups of methodologies, processes, rules, concepts and theories that attained a level of success in certain areas, and because of those successes, have been deemed as universal truths able to be applied anywhere and everywhere. Just because someone says something doesn’t mean it’s true. Moreover, just because “Company A” had success with a certain initiative doesn’t mean that “Company B” can plug-and-play the same process and expect the same outcome. There is always room for new thinking and innovation, or at least there should be.”

Best practices are not absolute. They cannot be. They depend on context. Not just that, given the ever-changing nature of the macroeconomic and sociopolitical scenarios that we work in, what holds good today, will probably not tomorrow. And we need to be able to appreciate that.

While we can – and certainly should – learn from successful practices, we cannot approach them as ready tailored solutions to be picked up and deployed. We have to keep innovating for our specific needs as a company.

A great example of this is Godrej LOUD. Godrej LOUD (Live Out Ur Dream) as many of you would know, is a radically different approach to business school recruiting, which we introduced four years ago. We were looking to engage more meaningfully with business school students in India. When our team studied existing best practices, they found that all companies were using different forms of business case studies and competitions to engage with students and then, basis that, make them recruitment offers, separate from the traditional recruitment process. While we could have fairly easily created a business case study of our own, we felt that it didn’t quite fit in with our approach to selection, which was to get to know the students better and figure out if they would be a good fit at Godrej.

So, we went back to the drawing board. And what we created was LOUD. We went to business schools and asked students to share their dreams with us. We offered the best ones sponsorship and a summer internship at Godrej. Why did we do this? Because we believe that passionate people will bring that same passion to their work and to Godrej. And that is what makes all the difference. LOUD has been a runaway success. It is uniquely, wonderfully Godrej, in a way that a business case study could not have been. We have met several amazing young people through this programme, some of who are now part of our teams. Apart from becoming an important part of our employer brand overall, LOUD has ensured that we are an employer of choice on business school campuses. We later launched LOUD for Godrejites – an in-house version for our own team members. Last week, our Indonesia team concluded a very successful finale of Godrej Indonesia LOUD, a version tailored for the schools that they hire from.

Also, take a look at some of the amazing work that Darshan and her talented design team are doing, collaborating with the marketing and R&D teams. They are not looking at just borrowing good practices from other companies. They are working on understanding emergent consumer needs and designing unique delightful products for them. A lot of our work on brands such as aer and BBLUNT has been truly path defining.

Shane Snow, cofounder of Contently and author of Smartcuts, has written a great article in Fast Company on this debate around best practices, called The Problem With Best Practices (http://www.fastcompany.com/3052222/hit-the-ground-running/the-problem-with-best-practices), which I am also sharing below.

Please read on…

Best practices don’t make you the best. They make you the average of everyone else who follows them.

In the late ’70s, Palo Alto-based entrepreneur Debbi Fields tried to get a loan to start a cookie store. Bankers turned her down with variations of the now-famous quote, “America likes crispy cookies, not soft, chewy cookies like you make.” If crunch was the disco-era best practice in cookie making-borne out by the popularity of Chips Ahoy!, which debuted in 1963—it didn’t stay that way. Fields eventually got her loan. Today, chewy cookies are a staple among modern bakers, and her signature variety is sold by over 4,000 employees in Mrs. Fields stores worldwide.

Best practices are only the best until they aren’t.

When best practices prove otherwise

Thirty years after Mrs. Fields opened her first cookie store, the British newspaper The Independent switched from large pages known as “broadsheets”—the size of a present-day New York Times—to a smaller “tabloid” format. For some 400 years, respected, “quality” newspapers had stuck exclusively to broadsheet, believing that was the format customers wanted.

As Harvard Business Review has reported, though, when The Independent made the switch, it not only saved money on paper, but more people bought it. British newspaper companies had begun using broadsheet in 1712, after the government placed a tax on the number of pages a paper contained. Even though the tax had been lifted in the 1800s, newspapers kept printing on large pages anyway.

The “best practice” is one of the business world’s most common conventions, but it’s often arbitrary and based mainly on habit—the result of conditions that no longer apply. Crunchy was a “best practice” for cookies because one popular company already sold them that way. Broadsheet was a “best practice” for newspapers because of a centuries-old law. But neither one was the “best” in any measurable sense at all.

Shaking the herd mentality

I recently had a look at the websites of several B2B marketing software companies to see what “best practices” they used. I was surprised to find that not only did every homepage look the same (wide-image backgrounds, carousel sliders, identical navigation items), but “ugly” appeared to be the reigning principle.

It was clear that one or two popular companies in the industry had designed their websites a certain way—perhaps even based on split testing and heatmaps, but likely not—and other companies had jumped on the bandwagon, saying, “If so-and-so is doing it, it must be the best way.” I even saw the pattern repeat itself a couple of months later when a market leader changed its homepage background to a moving image, and suddenly every other website in the category had a video background, too.

This kind of herd mentality is common outside of business as well—fads come and go, bandwagons appear and disappear. But like Fields and The Independent, we risk leaving a lot of money on the table if we place too much stock in best practices.

What’s wrong with the “best” approaches

Part of the problem is with assumptions. “If this wasn’t the best way of doing things, I’m sure it would have disappeared by now,” is a logical fallacy and an unfortunately common refrain.

The other part of the problem is that best practices are a misnomer. Often what we call best practices were at one point good or smart business moves, but we seldom do the work to determine how long they stay the “best” or whether they’re universally applicable.

If Mini Cooper had followed best practices when it relaunched its iconic coupe in the early 2000s, it would have released a Ford Escort. If Apple had followed best practices, it would have released a six-button mouse instead of the zero-button Magic Mouse that doubled its market share overnight. Best practices don’t make you the best. They make you the average of everyone else who follows them.

Finally, best practices are falsely self-perpetuating. A classic example is Hollywood, which has long assumed that movies with more stars are more likely to be big hits. Research from UCLA and SUNY, on the other hand, shows that this is not statistically the case for films with similar marketing budgets. However, movie studios still put more promotion behind the films they think will be big. Thus movies with ensemble casts tend to make more money, and the “best practice” gets reinforced.

I call this the “Best Practices Wikipedia problem,” as illustrated by Randall Munroe of XKCD:

History is clear that best practices can be enemies of growth. They allow us to take the lazy way out instead of pushing ourselves to be creative.

A cure for best-practice fever for those of us who can’t get out of our own heads (or are too addicted to benchmarking to do it any other way) is to borrow best practices from industries other than our own.

For example, when I was a college intern writing Google Adwords copy for marketing software, I beat competitors’ identical Google ads by borrowing techniques from online dating ads. I once wrote about a children’s hospital that borrowed best practices from a Formula 1 race team to solve a critical problem when best practices from other hospitals didn’t help. This is one way to engage in lateral thinking without having to be naturally out-of-the box yourself.

Looking to other, successful companies for inspiration is instinctual for most entrepreneurs. Another antidote to best-practice thinking is to attack problems using Elon Musk’s “first principles,” by stripping away assumptions, breaking problems down to their essence, and solving them as if for the first time. It’s more time consuming than copying your competitors, but it’s the way games get changed instead of simply played.

By definition, breakthroughs happen not when you follow conventions but when you break them.

So, if not best practices, then what? One of the things that Matt highlights in his article, is the need to move from thinking about ‘best practices’ to thinking about ‘next practices’. “Best practices maintain the status quo and next practices shatter it”.

Global business thinker CK Prahalad also talked about this in a HBR article a few years back. He argued that best practices would enable companies to catch up with competitors but not become market leaders. He put it vey aptly, “Best practices lead to agreement on mediocrity. Because all of them benchmark each other, we gravitate towards mediocrity in a hurry. What we really need to ask is what is the next practice, so that we can become the benchmark companies and institutions in the world”.

Remember that best practices in a way focus on incremental change. On the other hand, next practices can be more transformational and enable us to build for the future. So, I strongly encourage you to think about how we can make this shift in approach.

I am sure that there are many great examples of how we have, in different ways, been doing this. Do write in and share them with our team.

Comments